With a new testbed and several research projects underway, autonomous shipping is one step closer to becoming a reality. And DNV GL is working on developing the necessary rules.

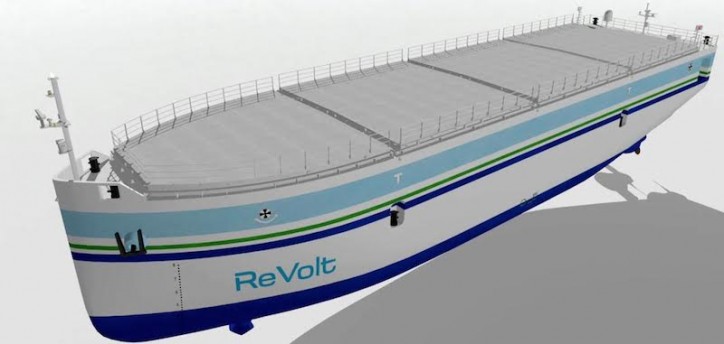

The little craft bearing the DNV GL logo gingerly braves the waves, as it skippers across the Trondheim Fjord under the watchful eyes of Kjetil Muggerud and Henrik Alfheim from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) in Trondheim. Both students are investigating how advanced control systems and navigation software could control an unmanned vessel, using a 1:20 model of DNV GL’s concept vessel ReVolt:

“Advances in sensor technology, data analytics and bandwidth to shore are fundamentally changing the way shipping works. And as operations are digitalized, they become more automated,” says Dr Pierre C. Sames, Director of Group Technology & Research at DNV GL.

Governments around the world are looking into unmanned shipping as a way to move more cargo to sea in order to contain the spiralling costs of road maintenance caused by heavy lorry traffic, not to mention air pollution. Norway has taken the lead in exploring innovative ways of tackling this issue and bridging its many fjords and sea passages to ease transit. Cost is a key consideration in all of this. In 2016 government agencies and industry bodies established the Norwegian Forum for Autonomous Ships (NFAS) to promote the concept of unmanned shipping. In support of these efforts, the Norwegian government has turned the Trondheim Fjord into a test bed for autonomous ship trials. Other nations, most notably Finland and Singapore, are pursuing similar goals.

DNV GL is in the midst of this development, following its mission to make sure the technologies enabling autonomous ships will perform to the benefit of humans, their assets and the environment.

The human factor

“If we look at recent advances in driverless car technology, the thought of trying something similar with ships does not appear too far-fetched. After all, water has at least one great advantage: there is less traffic than on roads and reaction times are usually longer,” says Sames.

The DNV GL experts identified three main factors that could positively influence the uptake of autonomous shipping: “Automation reduces the potential for human error. In addition, water transport can be cheaper and more energy efficient than moving goods on land.”

With a battery propulsion system, as seen on DNV GL’s ReVolt model, an autonomous ship would also be lower in maintenance than conventional ships. Additionally, an unmanned cargo vessel would also become more economical, as eliminating the superstructure would save weight and create more cargo space. Furthermore, unmanned ships may be used in hazardous operations, e.g. firefighting, or as stand-by rescue vessels for offshore structures.

Small craft with great ambitions

DNV GL has initiated or is taking part in various projects revolving around ship automation and autonomous control. The ReVolt project is one example; once all aspects of the autonomous control technology are mature, such a design could possibly be built and deployed as a 100 TEU feeder vessel on fixed routes in coastal waters.

Another project with DNV GL involvement, the Advanced Autonomous Waterborne Applications Initiative (AAWA), led by Rolls-Royce, is investigating a wide array of aspects relevant to commercial unmanned shipping – from technical development to safety, legal and economic aspects as well as societal acceptance. “At DNV GL, we are doing a lot of work to understand the potential risks that come with autonomous ship systems in order to set new standards for them,” explains Sames. “We are already working on developing requirements to be able to test and classify unmanned vessels in the future,” he adds.

The Autosea project of NTNU, supported by DNV GL, Kongsberg and Maritime Robotics, seeks to understand the performance of novel sensor systems and the error potential of autonomous control technology, especially collision avoidance. The NTNU scientists are also working on an autonomous craft for Trondheim harbour. The idea is to provide an on-demand ferry service to passengers and bicycles across a channel at the push of a button. Featuring electric propulsion, an induction-charged battery, GPS navigation and an anti-collision system, the craft will carry up to twelve persons. It is intended to function as a cost-saving alternative to building a bridge. A pilot study is planned for this year, and the ferry is expected to start operating in 2018/2019.

Meanwhile two commercial projects are nearing completion: Rolls-Royce is supplying automatic crossing systems for two DNV GL-classed double-ended, battery-powered ferries the Norwegian operator Fjord1 plans to commission in 2018. Both vessels will navigate autonomously under the captain’s supervision, and he has the option to take control at any time. The first ferry will still require human-controlled berthing, while the second one will be able to perform this task automatically as well.

The unmanned offshore vessel Hrönn, under construction at Fjellstrand shipyard for a Norwegian and UK consortium led by Automated Ships and Kongsberg, will also be delivered in 2018. The light-duty, fully automated utility ship will be deployed in a shuttle service for offshore installations but could be used for many other purposes, ranging from research to fish farming operations.

Furthermore, a plan to built the first unmanned and fully-electric container feeder ship was recently unveiled by Kongsberg and the Norwegian fertilizer specialist Yara. After her delivery, Yara Birkeland will initially operate as a manned vessel and start travelling between the Norwegian ports of Brevik and Larvik autonomously in 2020.

The challenges

Overall, autonomous shipping opens up great opportunities for the European shipbuilding and shipping industries. But new competencies have to be built before autonomous ships can become a commercially viable reality. Key research must be done to improve sensor technology, the acquisition of high-resolution ranging data and instrumentation accuracy. Software plays a very important role in this scenario by enabling situational awareness, a prerequisite for automated decision management. “While existing know-how from the aerospace and automobile industries can be leveraged, specific expertise in ship autonomy has yet to be built up,” states Sames. The research activities at NTNU, sponsored by DNV GL and industry stakeholders, are instrumental in creating a new generation of highly skilled ship autonomy experts.

Another concern is the operational availability of on-board machinery. No immediate repairs are possible on an unmanned craft so reliability of all mechanical and electronic components is of utmost importance. “In addition, having battery-powered unmanned vessels would eliminate movable parts from the power generation system and make them easier to maintain,” says Sames.

Segments that could see the first autonomous vessels in operation, include ferries or offshore supply vessels operating in coastal areas or smaller cargo vessels operating in short-sea-shipping.

However, the expert cautions that, as yet, there is no legal framework that governs the use of unmanned ships. DNV GL is developing a set of rules, but to avoid potential conflicts with international law autonomous ships will not be able to operate in international waters until the IMO develops appropriate regulations, which will take time. For the deep-sea segments, autonomous shipping is not an option today, says Sames. “These vessels travel distances that go beyond the range of battery propulsion, and they require well-trained crews on board who can respond quickly to any technical issue,” says Sames. “If an unmanned vessel had a technical issue in the Atlantic, it would take days to reach it and fix the problem. This would not be safe or economical,” he adds.

Additional crew support

However, advances in automation can benefit all industry segments in some way, even without fully autonomous control. In the future, some ship traffic could be controlled remotely from land-based virtual bridges – with one ship master overseeing several vessels at the same time. “But the most likely scenario is that the technology which enables autonomous ship operations will simply be an additional option for operation – meaning they could be used for specific purposes without fully replacing traditional, manned operations,” Sames suggests. “So for example, autonomous navigation and control systems could support the crew in steering a vessel, increasing safety and optimizing operational efficiency.”

Source: DNV GL